Global Financial Crisis

by Professor Throckmorton

for Intermediate Macro

W&M ECON 304

Slides

Introduction¶

Many economic recessions are preceded and accompanied by a financial crisis.

A financial crisis features an over-supply of credit, over-leveraged firms and banks, and asset bubbles, which eventually collapse and result in bank and firm failures.

If the financial crisis is severe enough, then it may trigger significant declines in aggregate income and employment, i.e., an economic recession.

Both the U.S. Great Depression (1929-1933) and Great Recession (2007-2009), or Global Financial Crisis, are recessions of this type.

For the Great Depression, an over-supply of credit fueled a stock market bubble, while for the Great Recession the bubble formed in the housing market.

Both recessions originated (mostly) in the United States but had a global impact because the U.S. is at the center of the global financial system.

Housing Bubble¶

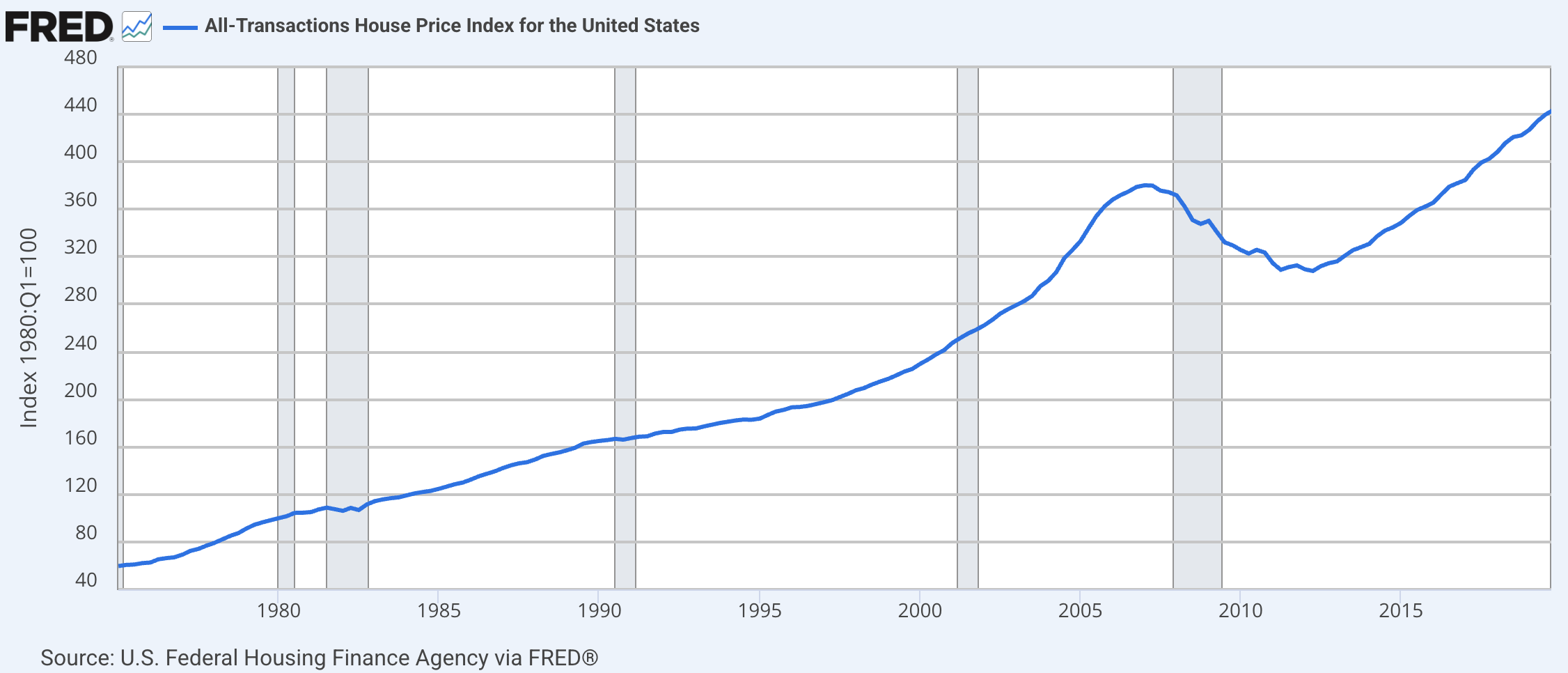

U.S. home prices rising nearly linearly until late 1990s

By 2005, home price bubble is forming

By 2011, market makes full correction, reverting back toward pre-2000 linear trend

Mid-2010s, home prices increasing as labor market recovers and economy grows

Q: Why did the housing bubble form?

After the tech bubble and early 2000s recession, the Fed lowered the short-term interest rate to 1%, which decreased mortgage interest rates.

Housing demand was fueled by subprime mortgages, which made up about 20% of new mortgages by 2006.

Mortgage lenders were willing to make these riskier loans because

housing serves as collateral and can be sold (foreclosed) in the event of default

housing prices are usually increasing, so value of mortgage is decreasing relative to house value over time

financial innovations coupled with an over-supply of credit allowed lenders to sell the mortgages and unload the risk

Housing Supply¶

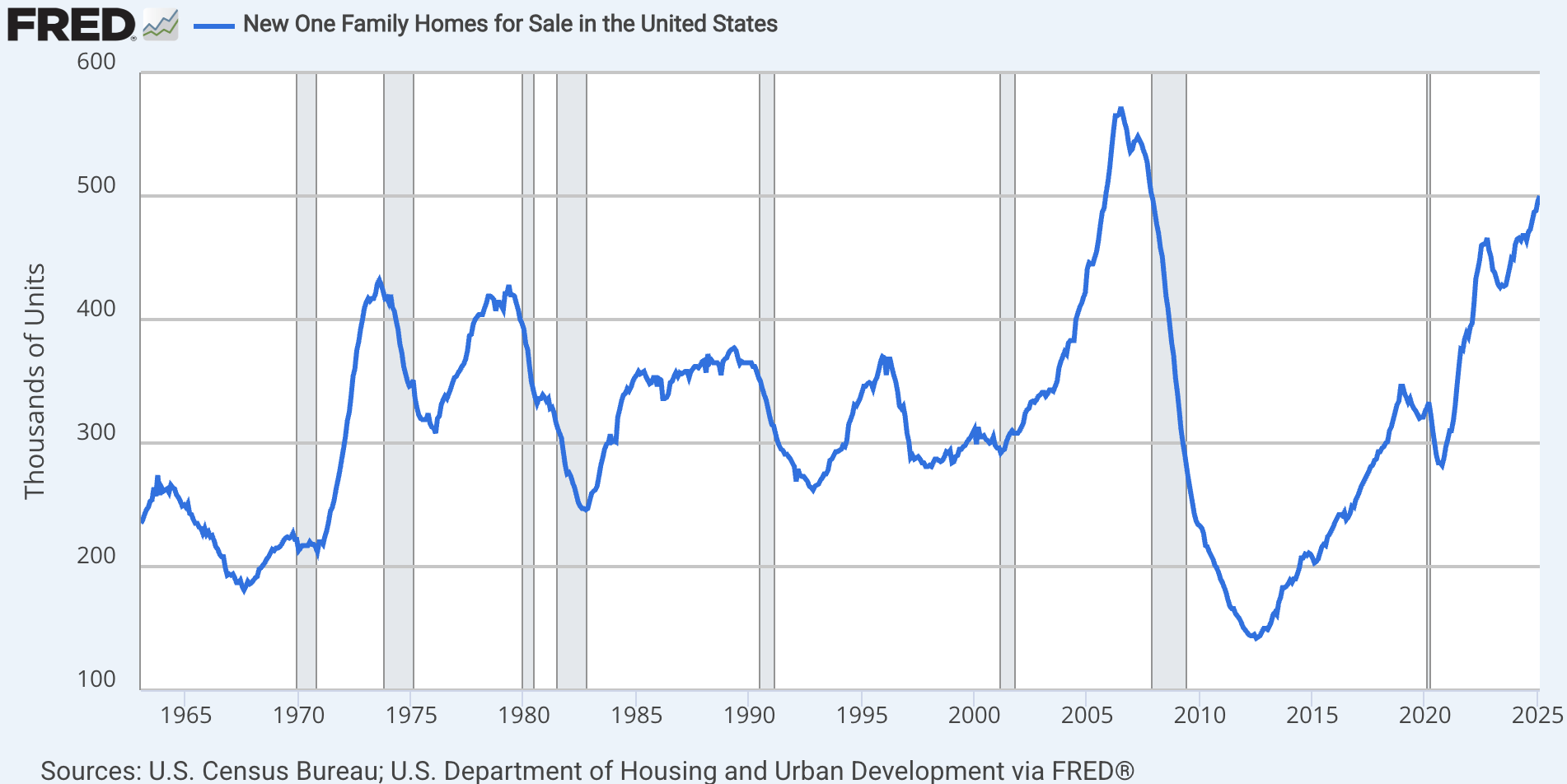

Housing supply is a good recession indicator, often plateauing before recessions

From 2003 to 2007, increased demand for housing lead to more construction in new one-family homes

But increase in supply was not enough to meet demand and stabilize home prices

Financial Crisis¶

Mortgage Debt

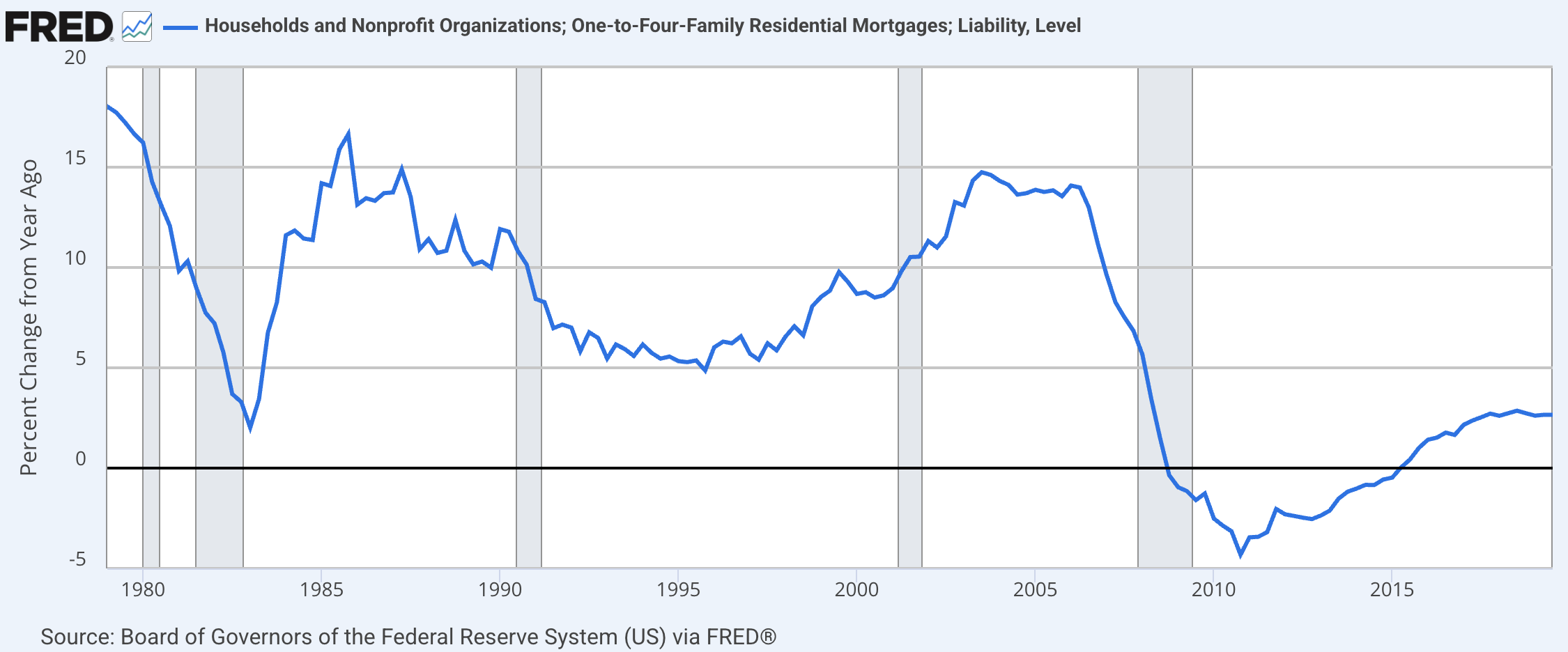

Rise in house prices accompanied by growing indebtedness of households

Mortgage indebtedness grows by 2-3 times as much in the 2000s than the 1990s

Mortgage Backed Securities¶

U.S. traditional lending model: local banks make loans to families in community

loan risk stays at that bank

local bank has best information about neighborhood/family

local bank would not want to loan to family unable to pay them back

Securitization: Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS) bundle up individual mortgages into securities that can be bought/sold in large volumes

local bank can sell mortgages to big banks (transfer risk)

big banks diversify risk by bundling mortgages from different places

Pensions/hedge funds/other countries can invest in U.S. housing market

Expanded lending: If more people want to invest in “safe” U.S. housing, then local banks can always sell their mortgages to (i.e., unload risk onto) bigger banks who bundle them into MBS.

Subprime Mortgages¶

People with a credit history have a credit score, e.g., FICO or VantageScore, ranging from 300 to 850

Prime mortgages: Mortgages given to families with good credit scores (660+) pay lowest/prime interest rates

Subprime mortgages: given to families with low credit scores who are more likely to become delinquent and thus pay higher interest rates

Credit score is largely determined by

length of credit history: a long history of making payments on time means a higher credit score

amount owed: a low usage of available credit means a higher credit score

U.S. mortgage lending was very relaxed and unregulated: No Income, No Job or Assets (NINJA loans, “no-doc”, “low-doc”)

Source: NY Fed, Center for Microeconomic Data, “Household Debt and Credit Report”

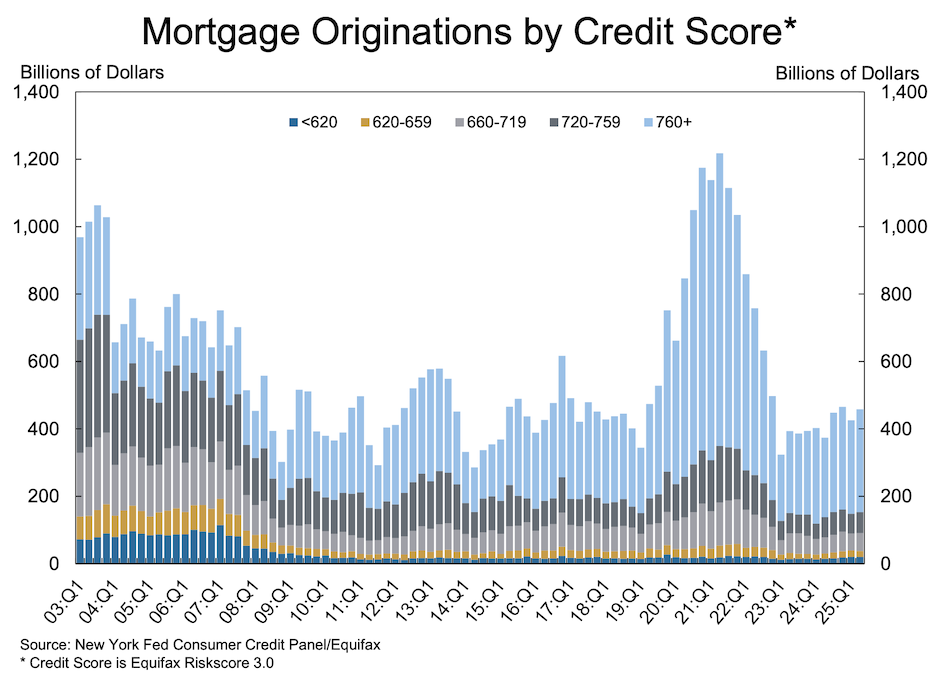

2003-2007, larger share of new mortgage $ in sub-prime market

2020-2022, huge increase in new mortgage $ given expansionary monetary and fiscal policies as well as COVID-related changes in household preferences

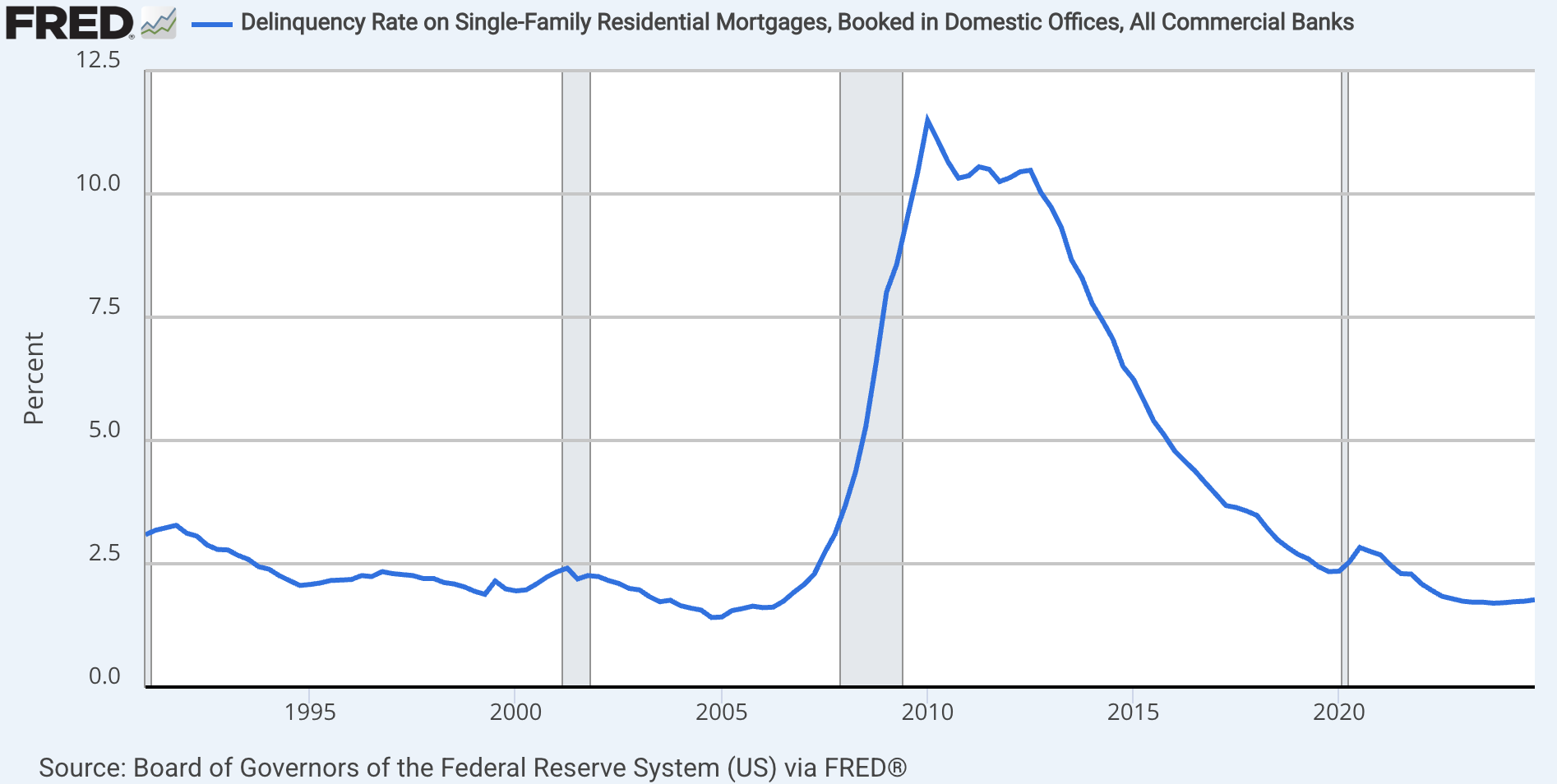

Mortgage Delinquency¶

Mortgages used to buy second homes, which one study estimates is responsible for “30 and 15 percent of the run-up in construction employment and house prices, respectively, over 2000-2006” (Garcia, 2019)

Subprime mortgages were concentrated in particular cities/neighborhoods (e.g., lower income or boom regions)

Adjustable Rate Mortgages (ARMs): “teaser” rates that reset after 2, 3, or 5 years to the market rate

people were surprised by very high mortgage payments (e.g., prime rates from in 2002-04 to by 2006-07)Underwater: mortgage owed exceeds value of house

walk away and foreclose (bank sells) the home

home prices fall furtherAll of these factors contributed to growing mortgage delinquency.

Delinquent loans are those past due thirty days or more

Pre-crisis delinquency rate on mortgages was 2.5%

After the housing bubble popped, about 1 in 10 mortgages became delinquent

Mortgage payment forbearance and foreclosure moratoriums did not exist during the financial crisis as they did during COVID.

Financial Innovations¶

MBS are only one financial innovation that played a role in the crisis. There are also:

Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO): securities that cater to an investor’s preference for risk, i.e., risk-free vs. risky, whose value comes from other securities, e.g., MBS

lets different kinds of investors participate in U.S. housing, further driving demand for more mortgages

“complex”: CDO value is derived from underlying MBS whose value is derived from underlying mortgages

Credit Default Swap (CDS): uncollateralized “insurance” where seller of the CDS, e.g., AIG, compensates the buyer in the event of default, e.g., Lehman Brothers

Structured Investment Vehicles (SIV): a way for banks to avoid financial regulation, increase leverage, and purchase risky securities

Rating agencies had difficulty assessing the value of complex financial derivatives and received fees from the same banks they must issue ratings for, which provides an incentive to give higher ratings

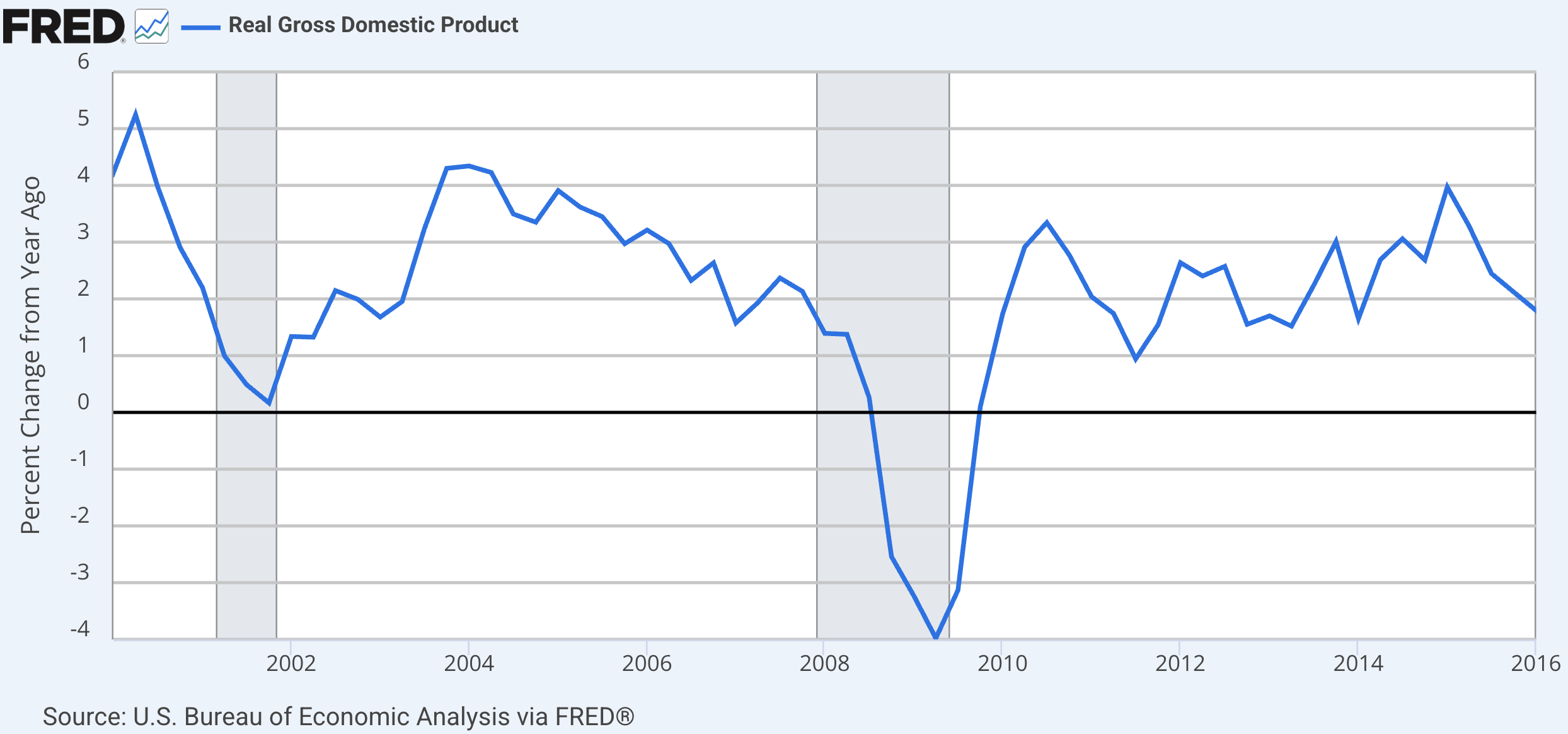

Great Recession¶

At trough of recession, real GDP growth was -4%

In 2010, growth recovered to pre-crisis rates

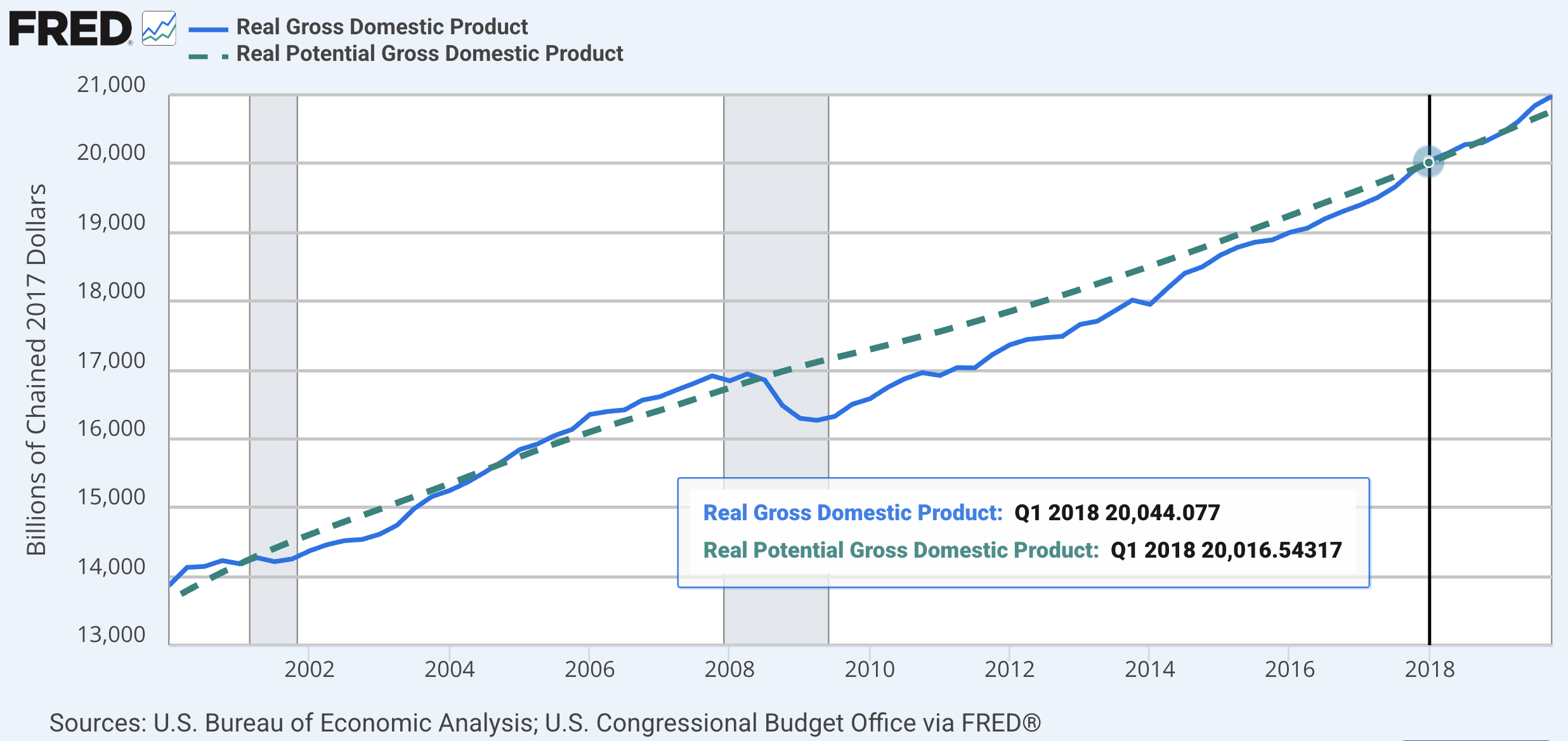

Recession pushed real GDP below potential

Full recovery of aggregate income took 9 years

Financial crisis led to 50% reduction in NASDAQ Composite Index

Stock market did not fully recover until 2011, about 2 years after trough

UR doubled in the recession, about 7.5M people lost jobs

It did not fully recover until 2016, about 8 years after the end of the recession

Unemployment for longer than 27 weeks persisted

It took even longer than UR to reach pre-crisis levels

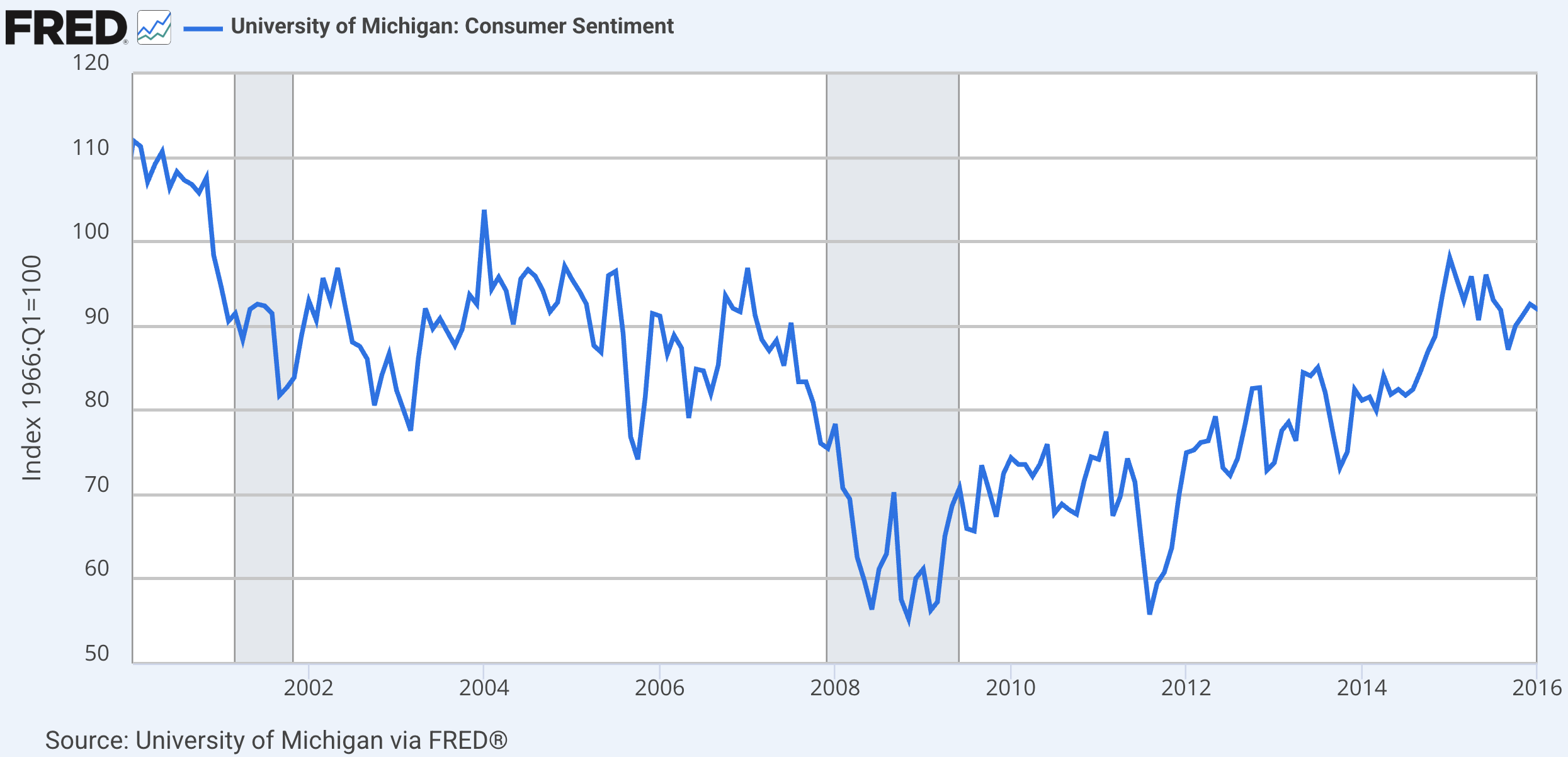

The consumer sentiment index fell from 90 to 60 during the recession

It recovered by 2015, just before the labor market

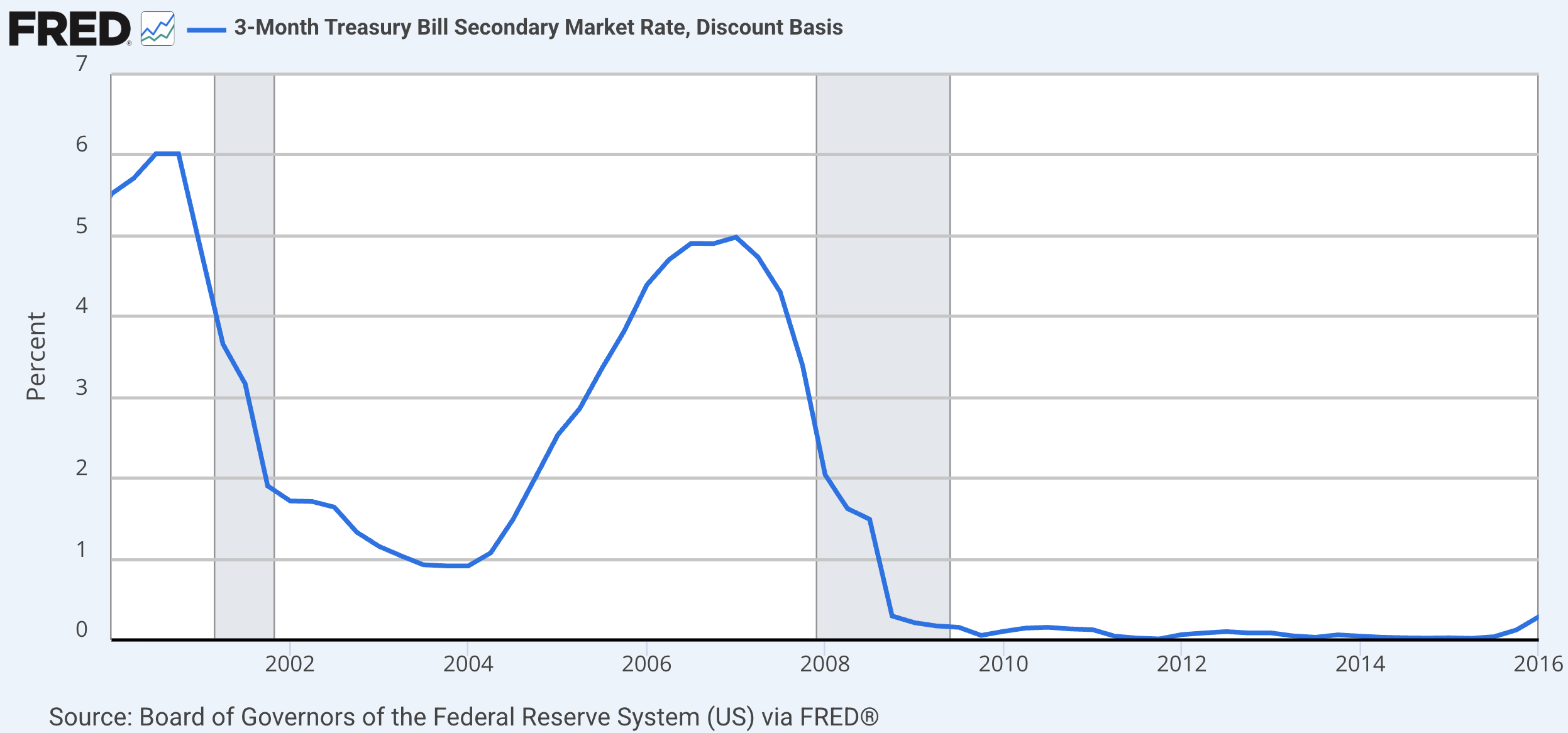

In 2008, the Fed lower short-term interest rates to near 0%, i.e., the zero lower bound

At the end of 2015, the Fed began to raise rates once the economy was finally back to normal

Policy Responses¶

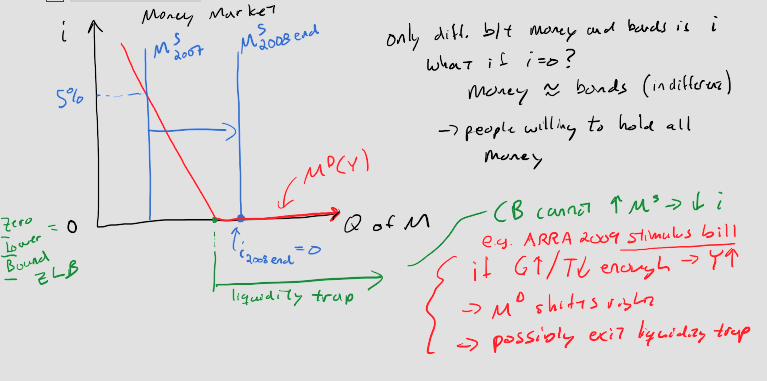

Monetary Policy: Fed sharply reduced its policy rate from to 0- (2008Q4)

Fiscal Policy: the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of Jan 2009 increased government spending (+B) and cut taxes (-B)

Other policies

Fed’s large-scale asset purchases (LSAP or Quantitative Easing) of MBS and long-term U.S. T-Bonds

Fed’s Term Auction Facility (TAF)

Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP): U.S. Treasury and Fed purchased assets and equity from U.S. financial institutions

FDIC guaranteed new (senior) debt issues by banks

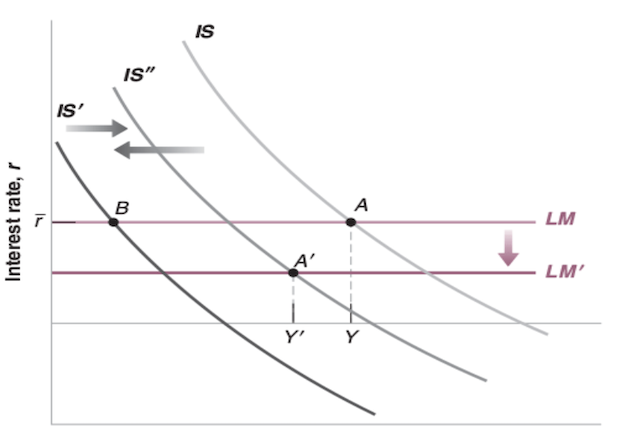

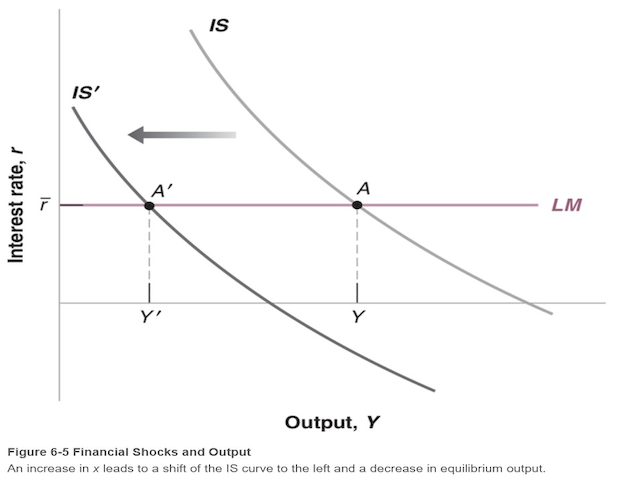

The following figure is from Blanchard, Macroeconomics (9th Edition, 2025), Chapter 6, Page 128

Decline in home and stock prices shifts IS left. is an equilibrium without policy interventions.

Expansionary monetary policy shifts LM down

Expansionary fiscal policy shifts IS right

Final equilibrium output, , is below pre-crisis level, (e.g., potential output)

Liquidity Trap¶

Liquidity trap: central bank cannot lower the short-run nominal interest rate by increasing the money supply

Zero Lower Bound (ZLB): when the short-run nominal interest rate equals its lower bound, i.e., in U.S.

But central bank might still be able to lower longer-term interest rates

And central bank acting as “buyer of last resort” still helps provide liquidity to markets and prop up asset prices to improve balance sheets

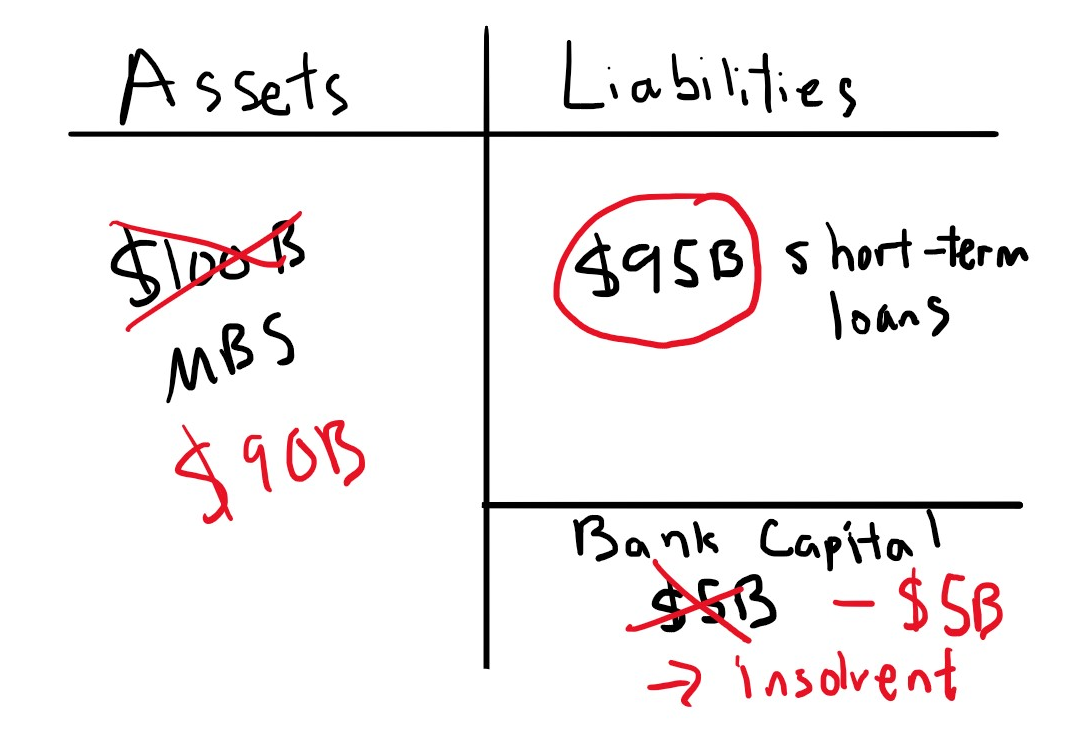

Balance Sheet¶

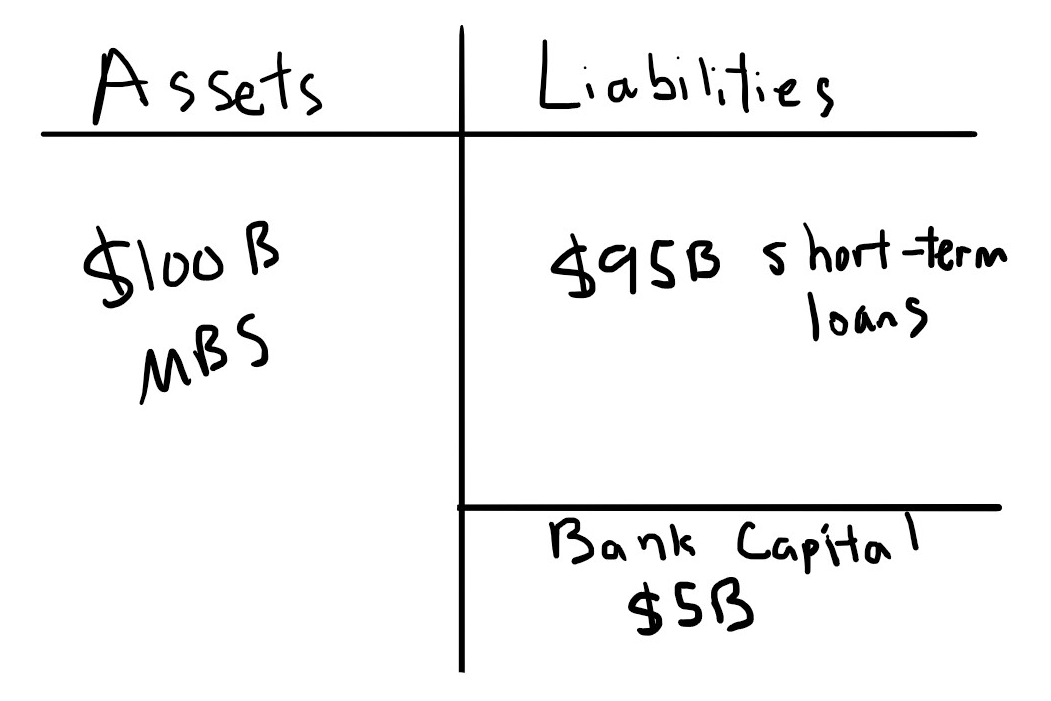

Balance sheet: Assets = Liabilities + Equity

Assets store value at market prices (mark-to-market)

Liabilities are financial obligations to others

Equity is what’s left if you sold the assets and paid off all liabilities

Equity belongs to the owners of the firm

Equity for banks is known as bank capital

Bank Failure

Suppose families become delinquent on mortgages

MBS (assets) fall in value by 10%.

mark-to-market: B in assets is now only B

Bank still owes B in short term

Equity/Bank Capital = Assets - Liabilities = B - B = B

Negative equity means the bank is balance-sheet insolvent

Capital Ratio

Capital Ratio = Bank Capital / Assets (Leverage Ratio = Assets / Bank Capital)

Investment banks were highly leveraged (e.g., leverage ratio = 30-40)

Thus, a small change (2-3%) in asset prices can threaten balance-sheet insolvency

In 2007, U.S. investment banks had no fixed minimum capital ratio like commercial banks, who are subject to capital requirements.

Regulators often close a commercial bank once its capital ratio falls below a critical threshold to protect depositors.

Balance-sheet insolvency can be resolved through

bankruptcy, which is easy for small banks and difficult for big banks

acquisition: big bank buys little bank, e.g., JP Morgan acquired Bearn Stearns investment bank (Mar 2008)

equity injection: somebody/thing gives capital to bank, increasing equity/bank capital

Different than Cash-flow insolvency: not enough cash on hand to pay creditors, which can be resolved by

transforming/selling assets, which if a lot of banks do, then asset prices fall

new liabilities, borrowing from other individuals, banks, or the Fed

new owners/equity injection, somebody/thing gives cash to bank and becomes an owner/increases ownership

Financial Crisis

In crisis, cash-flow in “dries up” and threatens cash-flow insolvency, e.g., delinquent mortgages reduce cash-flow on MBS and CDOs

Banks sell assets to get cash so they can stay cash-flow solvent

Banks sell other assets (not just ones related to mortgages) that still have value, which causes those prices to fall

A lot of banks selling a lot of assets is known as a fire sale and the assets become very illiquid because nobody wants to buy them

Also no one wants to (nor can even) loan to firms

Asset prices fall and reduce the value of existing assets on balance sheets, which threatens balance-sheet insolvency

Too Big to Fail: the insolvency of a big bank that would pose an existential threat to the financial system

Policies

The Fed acts as lender of last resort to provide loans to financial institutions so they stay cash-flow solvent

The Fed acts as buyer of last resort to provide liquidity to financial markets and prop up asset prices, which decreases chance of insolvency

Congress can approve loans to bail out banks and firms

Federal gov’t can become an owner of failing firms, e.g., Bear Sterns, Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and AIG (injecting equity and buying shares of stock)

Longer-term: increase capital requirements (lower leverage ratios, e.g., Basel Accords) to decrease chance of balance-sheet insolvency

Risk Premium¶

We’ve talked a lot about short-term risk-free rate, e.g., Fed funds or 3mo U.S. T-Bill

Risk premium: additional interest to compensate lenders for default risk, i.e., credit risk

Also term/liquidity premium: additional interest to compensate lenders for risk of lending long-term

long-term assets are less liquid than short-term assets

Investor who wants to sell long-term asset is exposed to price volatility

These premiums are additional channels to influence investment/consumption

reduce risk premium by buying assets backed by riskier securities, e.g, MBS

reduce term premium by buying longer-term securities, e.g., Treasury bonds

Recall the goods market in a short-run equilibrium

Now lenders demand risk premium

increases in recessions as profits fall and loans dry up

Fed can lower by buying assets backed by (or lending collateralized by) riskier securities

The following figure is from Blanchard, Macroeconomics (9th Edition, 2025), Chapter 6, Page 121

An increase in the risk premium raises the cost of borrowing to finance investment

For a given short-term risk-free rate, investment declines in the goods market

The IS curve shifts left

- Garcia, D. (2019). Second Home Buyers and the Housing Boom and Bust. Finance and Economics Discussion Series, 2019.0(29), 1–36. 10.17016/feds.2019.029